Introduction

Financial markets have become increasingly disconnected from society over the last few decades. The majority of financial transactions currently occur within the sector, amplifying value internally, but not adding value the wider community (Kay, 2016). This disintermediation comes with a number of challenges and raises questions around the purpose of finance. Firstly, this characteristic has caused the sector to predict risk in relation to the market as a whole, rather than based on the actual risk to society (Silver, 2017). This is inadequate as it bases risk calculations on historical financial data (Taleb, 2007) and outdated scientific information (Nusseibeh, 2017). The existential threat of climate change requires a different approach. Forward looking models that account for externalities must be created which help prepare for rapidly increasing climate risks.

Public equity markets will play a key role in mitigating climate change, although, as they have become larger and more complex a number of faults have developed which hinder this progress. Due to the complexity, investors have been unable to maintain the sorts of relationships which once existed with companies (Kay, 2016). This is amplified by the increasingly short-term approach to financial markets taken by some investors, as well as the growth in passive investment, which minimises traditional duties of stewardship.. These changes have moved investors away from the primary notion of ownership created by equity markets (Nusseibeh, 2017). With this loss of ownership qualities, accountability is also lost, as well as the intention behind financial ownership. Investors no longer act in the best interest for shareholders and wider society. This paper discusses a number of the strategies currently in place for bringing about changes to public equity markets to address climate change, however it is easy to see how such strategies may be translated to tackle other societal problems.

The Evolution of Responsible Investment

There are a number of terms that are used, both correctly and incorrectly, when referring to responsible investment. Often the user does not properly understand the terminology, and so terms are misused synonymously, without appreciating the nuances to each investment strategy. The most commonly referred to terms include: Socially Responsible Investment (SRI), Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG), thermatic investing, impact investing or, merely, responsible investment. The earliest of these strategies was SRI, which was adopted by Quakers and Methodists in the late 18th Century (Berry, 2013). The notion behind such a strategy was to exclude financing from activities deemed to be negatively influencing society, based on values initially established by the church. In the late 20th century SRI strategies gained traction as many fund managers were pressurized to refrain from investing in South Africa, due to the contribution such investment flows had on financing the apartheid (Schroders, 2016; Hunt et al. 2017).

The growth of alternative responsible investment strategies out of the roots of SRI has put off mainstream investors, who often fail to appreciate the differences generated through these newer strategies. As SRI is driven by values primarily and returns thereafter, there is the assumption that this approach is true across the broad spectrum responsible investment strategies, and that therefore, returns would be sacrificed in the achievement of certain portfolio values, undermining the fiduciary duty of investors (Hunt et al. 2017). This is a falsehood, as will discussed later on in the paper. Furthermore, by not investing in certain sectors, SRI strategies sacrifice portfolio diversity, which is believed to impede performance by contradicting Modern Portfolio Theory and through the subsequent enhanced risk (Silver, 2017; Hunt et al. 2017). These points do not discount the positive impact which SRI has had, and continues to have, however, by association, other strategies may be tainted by the belief that investing capital more responsibly entails sacrificing returns in the process.

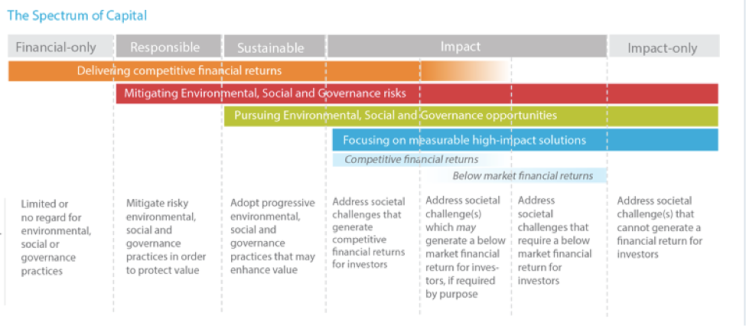

The ‘Spectrum of Capital’, Figure 1, developed by Bridges Ventures, gives a better indication of the potential responsible investment strategies currently in practice (Barby & Goodall, 2017). On the far left hand side of the diagram are traditional investment strategies, which show no consideration for environmental or social factors in decision-making. Moving right, under the ‘Responsible’ heading, would be what is considered ESG investing. This strategy seeks to supplement traditional investment methods by taking into account environmental, social and governance factors which are material to the fundamental value of the company. Thus, by understanding the composition of the company in a more holistic manner, a more accurate assessment of the value, and inherent risk, can be made. ESG investing does not discount any individual industry, however portfolio composition may be distorted based on the performance of

industries as a whole with regard to ESG factors. Going further across the diagram shows an increasing focus on the intention behind the capital to solve particular environmental or social issues. There may be a significant amount of crossover between these strategies and traditional SRI strategies, and additionally, it may be the case that portfolio diversity is sacrificed in the pursuit of these sustainable solutions.

Figure 1 – The Spectrum of Capital (Barby & Goodall, 2017).

The most established SRI strategy currently being executed is the fossil fuel divestment campaign. This has gained a great deal of attention, particularly amongst UK universities, where one quarter of institutions have enacted some form of divestment from fossil fuels (Carrington (1), 2016). Currently, investment funds valuing $5.2 trillion have now committed to divestment, doubling in the past year (Carrington (2), 2016). There are a number of reasons why the divestment campaign forms a logical argument. Firstly, from a scientific standpoint, it is borne out of an awareness of the potential for ‘stranded assets’ to evolve through oversupply of fossil fuels in changing market conditions (CTI, 2013). This oversupply occurs through an asymmetry between the known reserves of fossil fuels and the available carbon budget if we are to remain below 2 degrees Celsius. Thus, in order to remain within this budget, only 20% of current reserves are able to be exploited, severely endangering the revenue stream of fossil fuel companies (CTI, 2013). From this perspective, divestment of fossil fuels may be seen as aligned with the fiduciary duty of the investor (Hunt et al. 2017).

The second driver of the expansion of divestment activities is both a moral and a practical one. This being whether limiting warming to below 2 degrees is the most responsible course of action, when it may bring about negative financial results over the short-term, or if capital may be better deployed to other, more worthy causes in the immediate future (Lomborg, 2005). We may not be certain of the damage function created by an excessively warm planet; and whilst the majority of scientific and economic research supports the immediate action on climate change, it is right for these assumptions to be questioned and scrutinised (Covington & Thamotheram, 2016). It is only through this rigorous approach that models can be refined and trusted. Central to this moral and practical discussion are the concepts of responsibility and accountability. Two of the main challenges to tackling climate change are, as Mark Carney aptly described in his 2015 speech at Lloyd’s of London, the ‘tragedy of the horizon’ and the ‘tragedy of the commons’(Carney, 2015). This ‘tragedy of the horizon’ brings attention to the complexity of the timeline of physical climate impacts. Whilst predictions about the increase in precipitation, the frequency of extreme weather events or heatwave intensity are able to be made, the pace that these events will manifest are less certain, as they are ever dependent on the continuous actions of today’s society. The ‘tragedy of the commons’, which predates Mr. Carney’s speech, describes the problem caused by the shared responsibility to common goods, the climate in this case (Hardin, 1968). Currently the link between one’s actions and the subsequent effects on this massive and complex system are vastly detached from one another. This allows individuals to withdraw from taking accountability for their actions, both personally and through their allocation of capital. These complications around moral responsibility create numerous challenges for how best to manage the low carbon transition. The liquidity of public equity markets further complicates this issue, as investors’ positions and exposures to carbon risk can rapidly change.

There are three intended outcomes of fossil fuel divestment: political, reputational and financial (Hunt et al. 2017). Each of these outcomes is driven by the ability of the strategy to gain as much attention and support as possible, as it is only through the mass of the strategy that it has any real effect. From a political perspective, fossil fuel divestment is intended to send a signal to politicians about the severity with which major financial institutions are taking climate change. This signal aims to prompt politicians to alter the market to account for the externalities brought about by climate change, the solution most commonly referred to being carbon taxes. The reputational target is also reliant on mass. The voice of an individual investor or NGO carries far less weight than the $5.2 trillion worth of investors who have now committed to divestment (Carrington (2) 2016). This collective voice has far greater potential to damage the reputation of fossil fuel companies or bring about strategic changes. Nevertheless, reputational damage must be matched by a reduction in demand as a response to this collective action. Whilst in previous divestment campaigns, such as the South African apartheid, it was relatively easy to shift supply to other markets, it is comparatively more difficult to do the same for fossil fuels, which are so deeply ingrained in our current societal framework (Hunt et al. 2017).

The final goal of the divestment strategy is somewhat an aggregation of the other goals, and, as such has been left to last. The divestment campaign aims, through political mechanisms and public exposition, to negatively impact the financial performance of fossil fuel companies. Through the collective action of divestment, the intention is to drive down the share price by flooding the market with shares. Thus, this acts as a trigger to cause the correction of the stock, which appropriately takes into account the externalities caused by fossil fuel extraction and combustion. This is where the investment strategy is flawed. Due to the slight moral complexity of the strategy, it is undermined by being reliant on actors within the market all sharing the similar concerns. This is not to suggest in any manner that the concerns of the strategy are misguided. Conversely, the discounting of externalities, and subsequent increase in physical climatic risks poses great danger for those investors who seek out diversified portfolios, as these effects will be widespread across the economy (Nusseibeh, 2017). Thus, in order to minimise risk to the portfolio as a whole, investors ought to promote the goals of the divestment campaign in bringing to light the implications of externalities and amplification of risk to other equities. Nevertheless, such shared appreciation and values are not present within the financial sector. Therefore, despite the magnitude of commitments to divestment strategies, they are undermined by the fact that another, less morally inclined investor, is able to subsequently purchase the shares at a discount of the original price, and no price correction occurs (Hunt et al. 2017).

The Benefits of ESG Integration

It is important for investors to demonstrate this separation between ESG investing and other investment strategies in order to dispel the myth that it negatively impacts the risk-return profile of a portfolio. In order for ESG investment strategies to become a mainstream practice, empirical evidence must be presented on the effectiveness of the strategy at reducing volatility and increasing returns, rather than descending into the complex discussion of moral responsibility. This introduction of extra metrics into decision making, allows a step change to occur in investor behaviour. This is much more feasible than promoting rapid ideological shifts in the investment community, not to say that these would not be beneficial and welcomed.

There is an increasing amount of data to support the hypothesis for taking into account environmental, social and governance data into investment decisions (Clark, Feiner & Veihs. 2015). As the use of public equity to tackle climate change is the central topic of this paper, the key metrics that ESG analysts would therefore refer to would be carbon intensity and carbon emissions. Here again, there is strong evidence to suggest that good management practices of material environmental concerns have a positive impact on financial performance (Klassen & McLaughin, 1996). The carbon metrics show both the efficiency of the firm and the absolute emissions an organization is producing. Both of these are useful in gaining an understanding of the operational performance of the company (Clark, Feiner & Veihs. 2015). Firstly, the carbon intensity of the company may act as a good proxy for operational efficiency. A lower carbon intensity may signify a company using its energy more resourcefully, and therefore have reduced operational costs from energy expenditure (Porter & van der Linde, 1995). Secondly, as governments seek to address climate change through political levers such as implementing carbon taxes, those companies with lower absolute carbon emissions will be less directly affected by these policy developments. This allows them to innovate in new ways, without the burden brought upon competitors through increased expenditures (Hattori, 2017).

The separation between consumers and companies is often vast, and, whilst it is conceivable that climate-related issues may not be one of the primary factors in purchasing decisions, there is an increasing focus by consumers on the corporate social responsibility behaviors of companies. For the most part this extends to environmental scandals that have gained the most attention, such as the Mocando Oil Spill by BP, which sparked a boycott of the company in 2010 (Quinn & Mason, 2010). Although, companies such as Unilever, which focus on escalating green revenues also gain a competitive advantage through improving the brand reputation of the company by appealing to those customers who do factor in climate-related factors into purchasing decisions. Both from a controversy mitigation and product orientation perspective, the integration of ESG factors has been shown to be beneficial to operational performance (Clark, Feiner & Veihs, 2015). There is less evidence to support how individual ESG metrics impact operational performance, rather than from an aggregated approach, however, Friede, Busch and Bassen (2015) seek to address this in their meta-analysis. The paper deconstructs ESG performance into separate E, S and G factors, and analyses the proportion of studies which show a positive and negative correlation to operational performance. Analysing the E factor, the study shows 58.7% of studies demonstrate a positive correlation between high environmental performance and corporate financial performance, whilst only 4.3% show a negative relationship (Friede, Busch & Bassen, 2015).

The preceding evidence creates a strong theoretical case for enhanced environmental management being strongly correlated to corporate financial performance. The discussion does not, however, address the implications from a shareholder perspective, and whether this enhanced financial performance translates to stock price performance. Drawing such parallels is not a straightforward process, due to the wide range of factors beyond ESG that are considered in investment decisions. Nevertheless, ESG integration can support this decision, and the data for such strategies shows a number of benefits. For one, companies who perform well in ESG scores demonstrate decreased future earnings volatility and bankruptcy risk (Subramanian et al. 2017). The majority of studies use passive indices as an example of ESG, outperformance, both through actual tracking and through backtesting. This is because it is difficult to use active examples, such as those applied by Generation Investment Management or WHEB Group, as valid examples, as the outperformance shown by both of these funds is difficult to match with any sort of precision to ESG factors, despite their committed focus on applying such metrics.

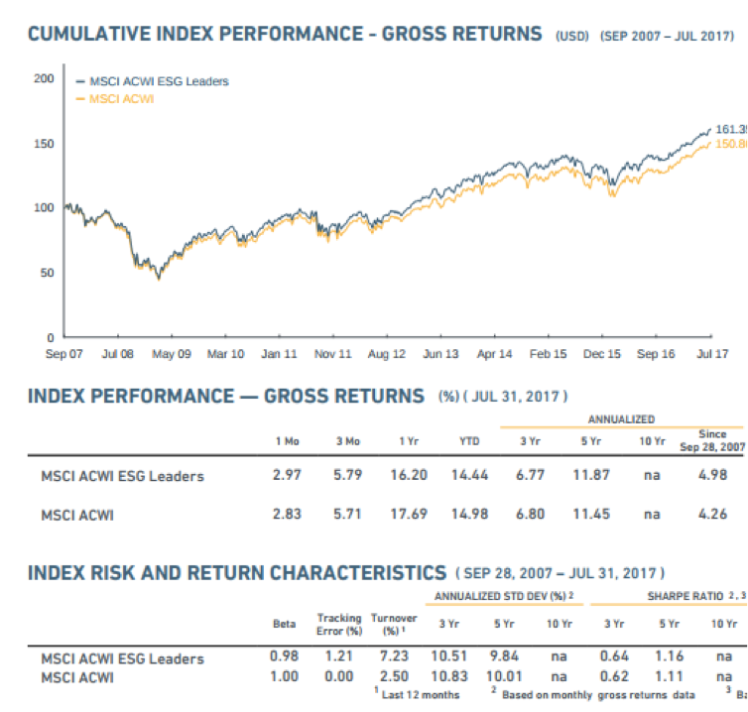

The rise of passive investing has both positive and negative implications for the mainstreaming of ESG integration. Firstly, it must be recognised that it is only through the initial innovation of active investors integrating ESG data, and creating the preliminary models, that passive funds were given the confidence to move into the space. Now that such passive funds are available, the uplift in performance and reduction in volatility are easier to be shown precisely. An example is shown in Figure 2, below.

Figure 2 MSCI ACWI vs. MSCI ESG Leaders Index (MSCI,2017)

MSCI are one of the data providers which have been collating and indexing ESG data. The other major data providers in this space include FTSE Russell, S&P and South Pole Group. MSCI have been chosen as an example due to the global coverage given by the All Companies World Index (ACWI). Using this as a benchmark it is easily compared against the ESG leaders index, which weights the index based on the ESG performance of companies (MSCI, 2017). The index displays better annualised returns, 11.87 versus 11.45 over a five year period, lower volatility, beta of 0.98 versus 1.00, and better risk-adjusted return, shown by a sharpe ratio of 1.16 for the ESG Leaders against 1.11 for the ACWI over a five year period (MSCI, 2017). These may seem like minor variances, however, in such a competitive market, create notable competitive advantages for these data providers.

The evidence from MSCI and other passive funds creates a useful empirical case for ESG integration. Nevertheless, it is important to note that through the creation of the indices a number of assumptions must be made where data is incomplete or unsatisfactory. For example, one of the most material factors for the financial sector, as assessed by MSCI, is carbon risk exposure. Currently the data for carbon risk exposure is not disclosed by financial institutions, therefore assumptions must be made based on the geographical distribution of the bank and sector distributions, with intrinsic carbon risk, within each of these countries. Clearly such assumptions do not take into account the idiosyncratic risk profiles of each project a financial institution is exposed to, which may distort the scoring system.

Despite this insufficient provision of data, the increased shift to passive funds has brought a number of benefits to the investment community. Both third party data providers, such as MSCI and S&P, as well as mainstream investors are pressuring companies for better disclosure. Historically this has taken place through various platforms such as CDP, formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project, and the Global Real Estate Sustainability Benchmark (GRESB). These are supported by a host of organisations which provide guidance on disclosure of sustainability information, such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the GRI. More recently, central bankers have begun to join the conversation about better disclosure, particularly regarding climate risk (MacKenzie, 2017). This has culminated with the final release of the Financial Stability Board’s (FSB) Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations in June of this year (TCFD, 2017). The recommendations were established by Michael Bloomberg, former Mayor of New York City, and Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, to reduce the information asymmetry between companies and investors, and raise the risk profile of climate risk to investors (Meltzer, 2016). It is hoped that the high profile backing of the TCFD recommendations will assist in creating a standardised process for climate risk disclosure.

There are two key benefits to be brought about by the increased requirement for data provision. Firstly, increased reporting of data by companies encourages the better management around these issues. This creates a virtuous circle of better data provision, better operational management and increased uptake of data, as it becomes more thorough and useful to investors. The second benefit, which is more specific to the TCFD recommendations, is a shift in the behaviour of investors around the conceptualisation of risk. This is created by the recommendation for companies to conduct scenario analysis around the macroeconomic trends of the low-carbon economy (Meltzer, 2016). This forward-looking attitude towards risk contrasts with the historical perception of risk previously integrated into financial models (Silver, 2017). These benefits will only enhance uptake ESG data in investment strategies.

Evidence of this growth is already visible. Research states that 60% of assets under management (AUM) in Europe are now assigned to ESG strategies (Subramanian et al. 2017). Additionally, signatories of the UN Principles of Responsible Investment (PRI) now represent around $70 trillion globally (UN PRI, 2017). These trends are expected to continue as capital shifts to millennials, who favour responsible investment strategies (Subramanian, 2017).

The Importance of Active Ownership

The PRI guides signatories through six principles (UN PRI, 2017). The first of these promotes the incorporation of ESG factors into decision-making and financial analysis. The second principle commits signatories to being active owners of their shares. Active ownership entails investors engaging with the companies within their portfolio on various corporate social responsibility issues (Dimson et al. 2017). There are a number of criticisms for ESG strategies, particularly those which do not include active ownership. The first is that, by seeking out industry best performers, based on ESG performance, and by not excluding any sectors, ESG integration does not fully support the transition to the low carbon economy. This failure is seeking to be solved by organisations such as FTSE Russell who are including calculations of ‘green revenue’ in the ESG analysis (FTSE Russell, 2016). This supports the reweighting of the index towards industries that generate revenues from sustainable products and services. For example, Tesla, who produce electric vehicles, may perform poorly with regard to certain ESG metrics, such as carbon intensity or gender diversity, although, the product, the electric vehicle, supports the transition to the low carbon economy, offsetting emissions which might have occurred if an internal combustion engine had been produced and sold. This factor should therefore be duly considered in the analysis.

Another criticism often given to ESG strategies that exclude active ownership is that they are particularly static. Due to the availability and consistency with which sustainability data is released, strategies which chose to include ESG factors can often be using information which is outdated. The increased attention to disclosure will assist in overcoming this challenge, however, there will continue to be a lag between operational and strategic changes within an organisation that address sustainability issues, and the integration of this information into valuations. This lag is exacerbated by the strategic changes only being fully integrated into the value once the results of these changes begin to materialise, through improved operational efficiency for example. Active ownership can help bridge this gap. Companies such as Hermes Investment Management have begun to overlay ESG data with data from company engagements (Clark, Feiner & Veihs, 2015). This data supports the investment analyst by giving an indication of the direction in which a company is heading in terms of ESG performance. Whilst it is by no means guaranteed that the commitments made in an engagement will be fulfilled, it does heighten the accountability and good faith between the investor and organisation, as well as giving an indication of future value.

The final criticism that is worth noting is that without integrating engagement into the ownership process, ESG strategies fail to add value to the financial system. Similarly to the concerns with divestment strategies, the owner of a stock matters very little if no engagement occurs. In many cases, for companies which may hold ESG concerns, it may be in the best interest of the company to have shareholders who pay little attention to these factors, so as to continue with their negative practices unimpeded. Alternatively, positive outcomes are able to be achieved for both investors and companies through engagement. There is evidence to support the notion that successful engagements can enhance stock price performance by an average of 7.1% over an 18 month period (Dimson et al. 2015; Clark, Feiner & Veihs, 2015). Executing a successful engagement, however, is not always straightforward as there are a number of dynamics to be considered. Kruitwagen et al. (2017) give an interesting account of how decision theory plays into engagements and how multi-stakeholder targets may complicate engagements. A successful engagement is brought about by the goals of the company and investor being well aligned, through efficiency improvements for example, creating a possible optimal situation. When these goals are misaligned, coming to a conclusion that involves the same degree of integrity and commitment is less certain and sub-optimal outcomes occur.

Conclusion

The paper discusses a number of strategies currently in place within public equity markets which contribute to the financial sector tackling climate change. The strategies which have been discussed are still niche, yet at the same time represent only relatively small changes to current behaviours. It may be the case that in order for the financial system to be ingrained back into society, as a sector which appreciates the value of all stakeholders equally, more radical shifts must occur. Positive changes in this regard are beginning to be established through strategies such as impact investing. Although for these to be more easily accepted by mainstream investors, more evidence of the value-adding benefits must be presented. The success in ESG data establishing this historical evidence provide much hope for this being a feasible goal. As shareholders revert to fulfilling their original place as stewards of capital, the unhealthy practices which had developed within markets will begin to be eradicated, being replaced by a healthier and more stable system.

Bibliography

Barby, C. and E. Goodall (2017). Bridging Impact-driven Investment Portfolios. World Economic Forum. Building a Strategy: Integrating Impact Investing in the Mainstream Investor’s Portfolio. Available Online at: http://reports.weforum.org/impact-investing-from-ideas-to-practice-pilots-to-strategy-ii/3-building-a-strategy-integrating-impact-investing-in-the-mainstream-investors-portfolio/3-2-building-impact-driven-investment-portfolios/. [Accessed on: 31/08/2017].

Berry, M.D. (2013). History of Socially Responsible Investing in the US. Thompson Reuters Sustainability. Available Online at: http://sustainability.thomsonreuters.com/2013/08/09/history-of-socially-responsible-investing-in-the-u-s/. [Accessed on: 31/08/2017].

Carbon Tracker Initiative (CTI) (2013). Unburnable Carbon – Are the World’s Financial Markets Carrying a Carbon Bubble? Carbon Tracker Initiative.

Carney, M. (2015). Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon – Climate Change and Financial Stability. Speech from the Lloyd’s of London. Available Online at: http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/speeches/2015/844.aspx. [Accessed on: 01/09/2017]

Carrington, D. (1) (2016). Fossil Fuel Divestment Soars in UK Universities. The Guardian Online. Available Online at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/nov/22/fossil-fuel-divestment-soars-in-uk-universities. [Accessed on: 31/08/2017]

Carrington, D. (2) (2016). Fossil Fuel Divestment Funds Double to $5trn in a Year. The Guardian Online. Available Online at: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/dec/12/fossil-fuel-divestment-funds-double-5tn-in-a-year. [Accessed on: 31/08/2017].

Clark, G.L., A. Feiner & M. Veihs (2015). From Stockholder to Stakeholder: How Sustainability Can Drive Outperformance. Published by Oxford University & Arabesque Partners. Available Online at: https://arabesque.com/research/From_the_stockholder_to_the_stakeholder_web.pdf. [Accessed on: 05/06/2017].

Covington, H. and R. Thamotheram (2016). The Case for Forceful Stewardship (Part 2). Available Online at: https://preventablesurprises.com/programmes/climate-change/. [Accessed on: 02/08/2017].

Dimson, E., O. Karakas and X. Li (2015). Active Ownership. The Review of Financial Studies: Vol. 28. Pp 3225-3268.

Eccles, R.G., I. Ioannou and G. Serafeim (2011). The Impact of Corporate Sustainability on Organizational Process and Performance. Available Online at: http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/the-impact-of-corporate-sustainability-on-organizational-process-and-performance. [Accessed on: 06/08/2017]

Edmans, A. (2011). Does the Stock Market Fully Value Intangibles? Employee Satisfaction and Equity Prices. Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 101. Pp 621-640.

Friede, G., T. Busch and A. Bassen (2015). ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More than 2000 Empirical Studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment: Vol 5:4. Pp 210-233.

FTSE Russell (2016). FTSE All-World Ex CW Climate Weighted Factor Index. London Stock Exchange Group. Available Online at: http://www.ftse.com/products/downloads/climate-balanced-factor-overview.pdf. [Accessed on: 03/09/2017].

Hardin, G. (1968). The Tragedy of the Commons. Science, New Series. Vol. 162. Pp. 1243-1248. American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Hattori, K. (2017). Optimal Combination of Innovation and Environmental Policies Under Technology Licensing. Economic Modelling Vol 64. Pp 601-609.

Hunt, C., O. Weber and T. Dordi (2017). A Comparative Analysis of the Anti-Apartheid and Fossil Fuel Divestment Campaigns. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment. Vol 7:1. Pp 64-81.

Kay, J. (2016). Other People’s Money: Masters of the Universe or Servents of the People? Published by Profile Books Ltd. 3 Halfords Yard, Bevin Way, London, WC1X 9HD.

Klassen, R.D. and C. McLaughin (1996). The Impact of Environmental Management on Firm Performance. Management Science: Vol 42.

Kruitwagen, L., K. Madani, B. Caldecott and M.H.W Workman (2017). Game Theory and Corporate Governance: Conditions for Effective Stewardship of Companies Exposed to Climate Change Risk. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment. Vol 7:1. Pp 14-36.

Lomborg, B. (2005). Global Priorities Bigger than Climate Change. Ted Talks Online. Available Online at: https://www.ted.com/talks/bjorn_lomborg_sets_global_priorities. [Accessed on: 01/09/2017].

MacKenzie, K. (2017). The Bank Regulator is Finally Putting Climate Change on the Risk Agenda for Australian Countries. The Climate Insittute. Business Insider Online. Available Online at: https://www.businessinsider.com.au/the-bank-regulator-is-finally-putting-climate-change-on-the-risk-agenda-for-australian-companies-2017-2. [Accessed on: 02/09/2017].

Meltzer, J.P. (2016). Financing Low Carbon Climate Resilient Infrastructure: The Role of Climate Finance and Green Financail Systems Global Economy and Development at Brookings. Available Online at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2841918. [Accessed on: 02/09/2017].

MSCI (2017). MSCI ACWI Leaders Index (USD). Available Online at: https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/9a760a3b-4dc0-4059-b33e-fe67eae92460. [Accessed on 29/08/2017].

Nusseibeh, S. (2017). The Why Question. The 300 Club. Available Online at: www.the300club.org/publications. [Accessed on: 16/06/2017].

Porter, M.E. and C. van der Linde (1995). Toward a New Conception of Environmental-Competitiveness Relationship. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol 09: No. 4. Pp 97-118.

Quinn, J. and R. Mason (2010). Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill: BP Faces Growing Calls For Boycott of its US Products. Telegraph Online Edition. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/energy/oilandgas/7742471/Gulf-of-Mexico-oil-spill-BP-faces-growing-calls-for-boycott-of-its-US-products.html. [Accessed on: 31/08/2017].

Schroders (2016). Global Investor Study: A Short History of Responsible Investing. Available Online at: http://www.schroders.com/en/insights/global-investor-study/a-short-history-of-responsible-investing-300-0001/. [Accessed on: 31/08/2017].

Silver, N. (2017).Blindness to Risk: Why Institutional Investors Ignore the Risk of Stranded Assets. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment: Vol 7. Pp.99-113.

Subramanian, S., D. Suzuki, A. Makedon, J. Carey Hall, M. Pouey, J. Bonilla and J. Yeo. 2017. ESG Part II: A Deeper Dive. Equity Strategy Focus Point. Bank of America Merrill Lynch Equity Research.

Taleb, N. (2007). The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable. Published by Random House (US) and Allen Lane (UK).

Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) (2017). Financial Stability Board (FSB) Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosure. Available Online at: https://www.fsb-tcfd.org/. [Accessed on: 03/06/2017].

United Nations Principles of Responsible Investment (UN PRI) 2017. UN PRI About. Available Online at: https://www.unpri.org/about. [Accessed on: 02/09/2017].